1. Introduction

Water is central in thinking about society, even more so when this substance is scarce, as in Utah. This state is an ideal location for studying the problems related to water access driven by climate change, policy decisions, and demographic factors. Global warming is expected to reduce the region’s yearly snowpack, decreasing water flow in the rivers. Consequently, these changes will diminish the ability of reservoirs to supply the required water, especially in dry seasons. Farmers and urban populations will have less water available to meet their needs. Additionally, drought conditions are expected to contribute to more intense wildfires, expand deserts, desiccate lakes, and foster worsening air quality. These changes will negatively affect the health of humans and animals (EPA 2016; Utah Division of Water Resources 2021).

Nevertheless, the impacts of climate change and natural variability depend not only on physical factors but also on how societies manage their water resources and prepare to face future threats. The southwestern United States is especially vulnerable to water shortages because of the high demand. The states of this region have developed and expanded their cities and economies by consuming more water than is available in the Colorado River basin. Hence, the water crisis is exacerbated by regional environmental planning problems (Kuhn, Fleck 2021; Fleck, Castle 2022; Schmidt et al. 2023). In this panorama, a central question arises: How can states address growing demands for water in the face of a need to reduce water use throughout the region?

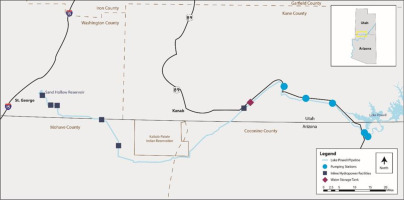

In Utah, construction of the Lake Powell Pipeline (LPP) has been under discussion for several years. The LLP is a water pipeline designed to address water supply problems in rapidly growing communities, such as Washington County, where St. George is located. It is estimated that it will cost about $2 billion to construct a 225 km, 1.8 m diameter pipeline that would transport approximately 103 million m3 (MCM) per year from Lake Powell to Sand Hollow Reservoir (Lake Powell Pipeline 2022). Numerous Utah officials and planners favor this project, assuring the public that these large-scale interventions are necessary. They indicate that according to hydrological models, there will be a water supply problem in southwestern Utah as the quantity of water in the Virgin River dwindles. Moreover, water demands are expected to increase dramatically due to the area’s high population and economic growth (Utah Division of Water Resources 2021; Lake Powell Pipeline 2022). Although water conservation is fundamental, these actors insist that Utah must focus on developing infrastructure to guarantee the region’s economic development.

Historically, the state has invested in infrastructure to guarantee water access. Thus, it is contended that the state must follow the same practice to support new citizens. It is also claimed that Utah has the right to take more water from the Colorado River because it has not exercised all of its use rights as established in the Colorado River Compact. Thus, it is argued that Utah can negotiate water withdrawals from the Green River to serve needy communities. Finally, this project will be paid for at meager interest rates, and it will generate a massive number of jobs in the region (Lake Powell Pipeline 2022).

In opposition to this project, critics assert that the scientific models used to justify these engineering works are based on insufficient, outdated, and erroneous data, and thus exaggerate the lack of water in the county, hide the high overconsumption, and do not account for the water that will become available from the transformation of agricultural land for urban expansion (Utah Rivers Council 2022). It is noted that the LPP would negatively affect the water supply of the Colorado River, which is already in a shortage crisis. This group of actors emphasizes that water rights were wrongly distributed among states at a time when the river’s water levels were unusually high (Kuhn 2020). It is also stressed that Indigenous nations have legal rights in the water planned for LPP (Penrod 2021).

Critics argue that the future water crisis in Washington County is a scare narrative used to finance costly infrastructure that all the region’s citizens will pay for. They argue that “There are many interests who stand to profit immensely from a billion in new spending and are happy to manufacture a fictitious water crisis for legislators” (Frankael 2014, p. 102-103). This project would not benefit all sectors of society, because household water consumption is a low percentage of total water use, which mainly supplies agriculture (Utah Rivers Council 2022). It is also suggested that this pipeline would encourage population growth and, in this way, generate an increase in the water demand (Smoak 2020). These critics indicate that Utah’s current water conservation strategies are minimal. If these efforts were encouraged and expanded, it would be possible to guarantee the water supply in the region without the need to build significant infrastructure (Kuhn 2020; McCool 2021; Olalde 2022; Utah Rivers Council 2022).

In the LPP controversy, actors for and against LPP have differing positions and hence challenge the objectivity of their opponents’ positions and data. We find divergent interpretations of the validity of current legal frameworks, the level of water consumption in the state, the effectiveness of the institutional responses to the water crisis, and the environmental and economic impacts of the project. The LPP seems to be a Tower of Babel whose stakeholders speak different languages in which the promises of development and sustainability collide with nightmares of ambition and scarcity.

It is necessary to point out that the groups for and against LPP do not have a final voice in the development of this project. The viability of LPP is not defined simply by the debate of technical and economic factors but by the coming effects of climate change and the political landscape of Utah and the Southwest. The rapid reduction of Colorado River flow, the water cuts of the seven basin states in response to the megadrought, and the upcoming development of a new management framework for the Colorado River Compact by 2026 all greatly influence developments and plans regarding the LPP. The priority of the states is to face the drought, not to increase water use and to further decompensate a system in crisis. For this reason, the future of this infrastructure project is uncertain. If its window of opportunity is currently closing, why should we study an infrastructure project that, at the moment, is only in the imagination of its proponents and critics?

Although LPP is on hold and may end up being buried not in the lands of Washington County but in Utah’s history books, this research shows that its controversies have significant intellectual and political relevance. Social theory teaches us that water supply is political and a primary source of conflict; as a well-known saying from the western United States illustrates: “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting.” What makes LPP particularly interesting is that it illuminates essential details regarding the political polarization within Utah, as to whether the water crisis should be addressed via infrastructure projects or conservation programs. At the same time, studying the LPP makes it possible to address important questions about present and future challenges facing the design of climate adaptation projects and to draw deep global connections. As river levels decline due to extreme droughts, the political storm over how to govern water increases. The construction of major-scale water pipelines remains a real possibility that water authorities are evaluating worldwide. For this reason, LPP offers insights into Western responses to water access problems that can be useful for policymakers, activists, and researchers. The attendant controversies have essential consequences as they become a historical precedent for political struggles and environmental conflicts. Currently, the eyes of the world are on how Utah responds to the water crisis.

Using a multimethod approach, namely contextual analysis of historical documents, interviews, literature review, and field notes, this case study examines the history, controversies, implications, and uncertainty in the construction of the LPP to show how the state of Utah has been addressing the larger problem: i.e., to respond to growing demands for water in the face of a well-documented need to reduce water use throughout the Colorado River Basin. This paper is divided into five sections to link this case’s overlapping contexts: (1) an introductory review of the political and technological history of the Colorado River; (2) a description of the arguments and controversies related to the construction of LPP; (3) identifying how the history of the Colorado River and LPP are deeply connected; (4) analysis of the properties of infrastructures to understand what is at stake in the materialization of this project; and (5) characterization of the complex political scenarios behind the negotiations of LPP between the federal government, the Colorado River basin states, the region’s Indigenous nations, and local authorities. Finally, this paper concludes with a reflection on how these controversies are part of a worldwide phenomenon whereby building local water infrastructure is prioritized, ignoring the need for more holistic river basin policies.

2. The control of the Colorado River

Access to water drives social life, so much so that the Colorado River has been the basis of development in the southwestern United States, given that the growth of its cities and industries in the 20th century depended on access to its waters. Starting in the Rocky Mountains, descending the canyons of the Southwest, combining with other important tributaries such as the Green River, and flowing into the Gulf of California in Mexico, the Colorado River has been exploited to boost and sustain the growth of populations in the most arid region of the country. The nation built a complex system of dams, canals, and reservoirs that allowed it to control and transport the river’s water to prevent flooding and ensure constant flow of the river throughout the year. Currently, 40 million people in seven states and Mexico depend on the river; its water is used to produce hydroelectric energy, sustain agriculture, and support domestic and industrial consumption in large cities inside and outside its basin (see Fig. 1).

The modern history of the Colorado River Basin is too complex for easy summarization, so this section provides only a brief background. Diverse historical conditions led to the multiplication of hydraulic technology in the United States. In the 19th century, river intervention was required to protect mining infrastructure and workers from natural fluctuations in water levels and flows. As hydraulic systems multiplied in the region, they supported the development of irrigation infrastructure for agriculture, and aqueducts for the growing cities (Isenberg 2006). At the end of the century, the federal government, through land grant laws, encouraged migration to the West using the promise of economic prosperity. Warnings of the danger that there was not enough water to support large populations or extensive irrigation systems in the West were not heeded because it was not politically popular to admit that many of these lands were arid. Many agricultural projects in the region began to fail. Yet, at the beginning of the 20th century, there was a shift in the technology and politics of the region; the era of large concrete dams for river control and water distribution began with the support of the federal government (Powell 2010). These infrastructure projects allowed the rapid industrialization of the West, so they became symbols of national pride, representing the economic reactivation of the country and the control of nature by human ingenuity.

To resolve regional disputes over water rights, in 1922 the seven states of the Colorado River Basin developed the Colorado River Compact to create the legal basis for management of the river. This treaty was designed to formalize water use so that states that did not have the technological capacity to use large amounts of water at the time retained future water rights. This administrative framework assigned different rights and obligations and artificially divided the basin into upper and lower regions accompanied by the implicit promise of upper basin storage at some point (see Fig. 2). In the year of the elaboration of the treaty, the average annual river flow was 20,200 million m3 (MCM) according to historical records of two previous decades. From this total of water, the commissioners defined that each basin had the right to use an annual 9200 MCM. States of the lower basin required those of the upper basin to guarantee their rights of access to water without regard to the variations of the river.

The lower basin’s rights to river water were distributed in fixed numbers: California (5400 MCM), Arizona (3500 MCM), and Nevada (370 MCM). The upper basin rights of the Colorado River were divided into percentages: Colorado (51%), Utah (23%), New Mexico (11%), and Wyoming (14%). In addition, a 1944 treaty granted Mexico 1850 MCM. In 1963, the Supreme Court recognized the water rights of Indigenous nations for the first time. However, legal struggles to legalize and enforce these rights, apportioned from state allocations, continue. The laws governing the Colorado River are called the Law of the River. This complex legal framework created the political conditions that in the 1950s led to the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam; the dam was built to accumulate surplus water from the Colorado River so that the Upper Basin states could guarantee the delivery of water to the states of the Lower Basin in times of drought (Powell 2010).

Throughout the world, connecting populations through hydraulic infrastructure is a way of creating and governing them because, as Appel et al. (2018) mention, the design and construction of these projects require imagining and defining a population that materializes from the daily flow of water and shared social aspirations. In this way, “Alignments of the pipes, politics, laws, and policies materially gather, constitute, and manage the population of the city” (p. 22). In the case of the Colorado River Basin, its landscapes have been profoundly modified by human interests, so its history can be seen as a product of the quest to know, predict, and manage the river’s flow, employing large-scale hydraulic technologies and the Law of the River to support and control the economic development of large populations in arid environments.

The shape of the basin landscapes illustrates how the impetus for control of rivers simultaneously drives the economic flourishing of societies and generates new scientific and political challenges that threaten their well-being. The region’s states currently deal with the unexpected material consequences of past political decisions and the effects of anthropogenic climate change. It is estimated that since 1880, the Colorado River has lost 10.3% of its water, and in the past two decades of megadrought, an amount equal to Lake Mead’s capacity (39,400 MCM) (Bass et al. 2023). For this reason, the basin states are faced with complex decisions to reduce water demand.

3. The Lake Powell pipeline controversies

Based on the Law of the River, Utah has argued that because it has rights to 23% of the upper basin allocation, it should still have 493 MCM of undeveloped water. Faced with future threats of water shortages in the center and south of the state, Utah has sought to develop new infrastructure projects to extract water from the Colorado River. In 2006, Utah passed the Lake Powell Pipeline Development Act (Utah Code 73-28). This legislative act justified the need to develop pipelines to transport water from the Colorado River to Washington County and to assign general planning guidelines and institutional responsibility to the Utah Board of Water Resources for constructing this project.

The LPP is designed to ensure Washington County’s medium- and long-term water supply. This infrastructure would consist of a buried 1.8 m diameter, 225 km pipeline transporting 103 MCM of water from Lake Powell in Arizona to the Sand Hollow Reservoir (see Fig. 3). According to its promoters, the approximate cost of this project would be between $ 1.1 and $1.7 billion, initially assumed by the State of Utah and repaid in the future with taxes from county citizens. So far, Utah has invested about $40 million in technical studies for the feasibility and preliminary designs of the project. The Utah Division of Water Resources proposes the development of LPP, and the Washington County Water Conservancy District leads the project. Both institutions, along with stakeholders in favor of this project, argue that it is necessary to build LPP for the four main reasons outlined below.

I. CLIMATE CHANGE

Increasing temperatures threaten to reduce the flow of the Virgin River, on which Washington County depends, so this primary water source will not be sufficient to guarantee the region’s water supply in the future. The general manager of the Washington County Water Conservancy District defended the construction of LLP, stating that extreme drought and fluctuations in the local river threaten the social development of its community (Lake Powell Pipeline 2022).

II. POPULATION GROWTH

The county’s water sources must be diversified due to its rapid population growth. The Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute (2022) expects Washington County to grow from 200,000 residents in 2020 to 500,000 by 2065. In addition, there is a high population of seasonal residents and tourists who visit its golf courses and the region’s national parks. Therefore, water demand will exceed supply in the coming years.

III. CONSERVATION WILL NOT BE ENOUGH

Although Washington County citizens have reduced their water use in recent years, it will only delay water shortages for a few years, even if they meet regional conservation goals (Utah Division of Water Resources 2021).

IV. THE REGION’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The only way to ensure Washington County’s economic growth is to guarantee a stable water supply. Furthermore, this infrastructure would positively impact the region, reducing the county water consumption by increasing the local cost of water. Moreover, state loans would have low interest rates, and this investment would create numerous jobs throughout the region (Lake Powell Pipeline 2022). In addition to the Utah Division of Water Resources and Washington County Water Conservancy District, there is support from the districts of Central Utah, Jordan Valley, and Weber Basin in a collective organization called Prepare60. This project is also championed by Congress members such as Senator Mike Lee (R-UT), Senator Mitt Romney (RUT), Representative John Curtis (R-UT), Representative Chris Stewart (R-UT), and Governor Spencer Cox.

The main strategies used by interest groups in favor of LPP have been to elaborate and socialize technical reports on costs and feasibility that justify its development, lobby to gain the support of state legislators and organize events in the local community of Washington County to publicize the benefits of this project. In 2021, The Spectrum surveyed 400 city residents about their perceptions of LPP (Meiners 2021). This poll found that 22% did not know about the project, 35% knew a little, 55% knew enough, and only 12% knew the proposal in depth. 59% support it, 35% are very supportive, 35% have some level of opposition, and 19% are very opposed. These figures partially indicate that while most citizens support it, they do not want to pay for it.

LPP is a highly controversial infrastructure project in Utah, as various environmental organizations, academics, Indigenous nations, and states oppose its construction. In recent years, the Utah Rivers Council has led a highly critical citizen study of LPP development, while other environmental organizations such as Conserve Southwest Utah, Glen Canyon Institute, Western Resource Advocates, Center for Biological Diversity, Great Basin Water Network, Save the Colorado, and Sierra Club are also against this project. Renowned academics from the region, such as Eric Kuhn, John Fleck, Daniel McCool, Gabriel Lozada, and Gregory Smoak, have expressed concerns about the negative impacts of this project. In addition, Indigenous nations such as the Ute and Navajo, along with the other six Colorado River Basin states, oppose this project due to legal conflicts over the rights to use the river. In general, there are four significant criticisms of LPP.

I. UTAH HAS NO MORE RIGHTS ON THE COLORADO RIVER

There is a reduction in Colorado River flow because states in the basin have used more water than is available. Therefore, building LPP would further reduce the level of a dwindling river and create more significant supply problems in a system already in crisis.

II. THE JUSTIFICATION FOR THE PROJECT IS BASED ON MISGUIDED FINANCIAL AND SCIENTIFIC DATA

The cost of LPP is higher than the project promoters claim, possibly reaching $4 billion. The critics also question the validity of model projections of the future demand for water since the models are based on erroneous and old data, and previous models have been wrong (Utah Division of Water Resources 2021). For example, the Wasatch region was initially projected to need new water supplies by 2015 but is now projected to have sufficient water until 2060. Moreover, the construction and operation of LPP would negatively affect ecosystems and endangered species in the region; the water diversion could also distribute invasive species in Utah.

III. WASHINGTON COUNTY IS NOT TRANSPARENT WITH ITS WATER USE DATA

Washington County has diverse water sources, not only the Virgin River. A drastic reduction in its supply is not expected due to climate change. A high rate of water waste in Washington County needs to be addressed, and its conservation goals need to be more ambitious. In addition, to justify LPP, the county exaggerates its current consumption and future demand, while failing to account for new water available through converting agricultural lands. Likewise, it is not considered that if water demand is reduced, it would not be necessary to build the pipeline (Utah Rivers Council 2022). Critics claim there would be enough water to support population growth with adequate management and water conservation, for example, by increasing the cost of water consumption and eliminating secondary water systems used for landscaping.

IV. UTAH HAS NOT RESOLVED ITS LEGAL PROBLEMS OVER ITS WATER RIGHTS

The State of Utah promised several decades ago to develop the Central Utah Project that would deliver water to the Ute Indian Tribe, but it has not fulfilled that promise and instead has prioritized LPP. If it is possible to obtain new water under the Colorado River Compact, critics affirm that it must be prioritized to comply with agreements with Native American Tribes.

Interest groups opposed to LPP have used various strategies to influence public opinion. They create multiple scientific reports on the shortcomings of the technical justification of LPP, participate in academic events in which they communicate points of view critical of this project, take legal action such as suing water districts that finance lobbies with public funding and have actively expressed their concerns in the open comment sections of federal and state reports related to LPP. Given the problems of water management in Utah, these actors are calling on the state to reject this project, declare a moratorium on diversions and dams, and radicalize the region’s conservation goals to respond to the water crisis.

LPP’s defenders argue that its critics have engaged in selective readings of their arguments so that they take the data out of context. This is a complex debate because different stakeholders have conflicting ideas about the interpretation of legal frameworks, the political will of Utah water conservation and its achievements, and the future social, ecological, and economic impacts of LPP. The most significant disagreements in this controversy are over water consumption rates in the state and the scale of climate change risk (to explore these controversies in greater detail, see Perdomo 2024a-b). These are the central scenarios defining opinions about whether Utah should prioritize its efforts toward either extensive infrastructure development or water conservation projects.

In 2015, economic studies by Utah professors began to cast doubts on Washington County’s financial ability to pay for the construction of LPP. To have more precise criteria when making decisions about the future water infrastructure, Utah state legislators ordered several investigations to evaluate the objectivity of their water data and the economic cost of LPP. In the same year, one independent audit identified that Utah did not have reliable data to project future water demands, and in 2019, another audit found that LPP would be financially sustainable only if taxes were increased and population growth maintained for fifty years. Amid this review of technical data, LPP has slowly advanced in terms of regulatory approvals. At the same time, the gradual reduction of Colorado River flow generates more citizen concern about water use in the region.

In 2016, the Utah Board of Water Resources (UBWR) initiated the process to obtain an approval permit for LPP. Its studies were submitted for evaluation to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission because multiple hydroelectric stations were planned in the original design. In 2017, the commission accepted the application but stated that it only had jurisdiction over the stations. In 2019, the Department of the Interior, after a request from the UBWR, designated the Bureau of Reclamation as the institution in charge of conducting LPP impact studies, because the UBWR modified its design by eliminating hydropower stations to reduce the project’s environmental impacts.

4. The environmental uncertainty of the Colorado River

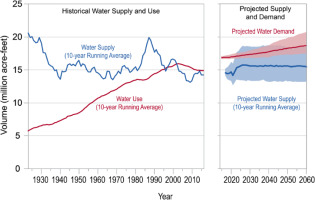

Over the past two decades, residents of the Colorado Basin have witnessed a gradual reduction in river flow due to climate change, regional planning problems, and population increase. According to the Bureau of Reclamation projections, the river’s water supply gap and its demand will increase in the following years (see Fig. 4). An essential aspect that explains the current crisis is that the river’s water rights were overallocated. In 1922, the Colorado River Compact commissioners distributed river rights with inaccurate data and ignored scientific precautions, which led them to establish fixed water use figures for the basin despite the river’s natural variation (Kuhn, Fleck 2021; McCool 2021). Hence, this legal framework cannot deal with present environmental conditions because it encourages the use of more water than is available. Currently, representatives of the states of the Colorado River Basin recognize this problem and seek to solve it within the legal opportunities of the Law of the River.

Fig. 4.

Historical supply and use and projected future Colorado River basin. Water supply and demand. Source: Bureau of Reclamation (2011).

In response to the drought at the beginning of the 21st century, the basin states designed technical criteria for coordinated management of the Colorado River reduction at Lake Mead and Lake Powell in the 2007 Colorado River Interim Guidelines. Based on the river’s water level decrease, each state of the basin should reduce its water use to keep the dams in operation. Expanding these guidelines, and in response to an increasingly extensive drought, in 2019 the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan was agreed upon, with the states of the basin and Mexico committing to more conservation strategies (neither of these two plans was designed with the participation of the indigenous communities of the basin). The new environmental conditions of the 21st century are forcing the basin states to develop a more coordinated water management strategy. These immediate actions are planned to keep the dams running until a new management framework for the Colorado River is agreed upon in 2026.

In June 2020, the Bureau of Reclamation published the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for the LPP and received public comments through September. This document is essential to the approval of LPP because the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires that infrastructure works on federal lands must evaluate and consider the environmental and socio-economic impacts of these projects along with public comments. Although the draft mentions that construction of LPP is viable and that new water supply sources are needed in Washington County, it also identifies the possible consequences of the different routes LPP can take. This report found that LPP could disturb Indigenous and recreational communities and negatively impact sensitive species in the region.

In mid-2020, the Trump administration ordered federal agencies to speed up the environmental review processes of large infrastructure projects in the nation, such as LPP. In September, a group of environmental organizations named Lake Powell Pipeline Coalition produced a report critical of the DEIS, arguing that it had extensive deficiencies in its analysis that prevented seeing the broad dangers of LPP. In addition, the other six Colorado River Basin states sent a letter to the Department of the Interior requesting that decisions about LPP not be made until their legal and logistical concerns were resolved to avoid legal conflicts. Later, UDWR asked the Bureau of Reclamation to extend the decision-making process so that it would have time to review the public comments on the draft in more detail.

In mid-2021, the water crisis worsened in the region. The southern part of the Great Salt Lake reached its lowest level in recorded history, and the governor of Utah decreed an emergency drought and asked people to “pray for rain”. In August, the Bureau of Reclamation made the first-ever water shortage declaration for the Colorado River, following the guidelines established in 2007. This action triggered mandatory cuts in the Lower Basin states, and the emergency UDWR Division of Water Resources introduced Utah’s Water Resources Plan, which warns of the dangers of diminishing water supply in the southern part of the state and justifies the urgency of building LPP.

At the beginning of 2022, the media popularized investigations finding that the megadrought in the Western United States between 2000 and 2021 was the worst in 1200 years. In the middle of the same year, further raising regional concerns, the Bureau of Reclamation published the 24-Month Study of water levels in the Colorado River. The worst-case scenario foresees Lake Powell and Lake Mead so low that they could reach dead pool levels in summer 2023. In response to these projections, the Bureau was forced to release more water from upstream reservoirs, hoping to increase the water level of Glen Canyon Dam and encourage more significant conservation by purchasing water rights from the Lower Basin so that Lake Mead water is not used. Amid this environmental crisis scenario, the Utah water authorities recognized that the negotiations on water supply shortages with the other states would affect the development of LPP.

In May 2023, due to institutional pressure from the federal government, the Lower Basin states, after lengthy negotiations, agreed to receive federal funding to conserve 3700 MCM of the Colorado River until 2026. In April, the story of the water crisis in Utah was temporarily inverted by spring melting of a record-breaking snowpack, whence the Governor of Utah declared a state of emergency due to flooding. In June, the Great Salt Lake had risen five feet since November, so boats returned, which had been retired in 2022 due to the drop in lake level. Scientists viewed this water relief with caution. Although the small reservoirs in the country’s Southwest recharged, this winter was abnormal, and there was still a vast water deficit. The annual natural flow of the Colorado River in the past two decades has dropped to 15,400 MCM per year, but the consumptive uses and losses were 18,600 MCM per year (Schmidt et al. 2023). Scientists warn that in the following decades, the basin will tend to become drier and hotter, changes in precipitation are still uncertain, and there will be a further decline in river flows caused by the direct relation between increasing temperature and decreasing runoff (Udall, Overpeck 2017; Bass et al. 2023). In the near future, Lake Powell could be depleted unless water consumption in the region is quickly reduced to extend the functioning of this reservoir. Therefore, new water management strategies, improved hydrological models, expanded conservation strategies, and public education on this topic are needed (Osezua et al. 2023).

There is still no precise date when LPP’s Environmental Impact Statement Supplemental Draft will be released or whether it will precede the final report for later obtaining rights to access Green River water stored in Flaming Gorge Reservoir. Scientific and political debates about the Colorado River are focused on taking rapid response actions to avoid reducing the river’s water level. These environmental contingencies leave the construction of LPP uncertain. The changes in the Colorado River Compact by 2026 will modify the capacity of Utah to develop water through infrastructure projects.

5. What does infrastructure hide?

The water supply of cities in the southwestern United States depends largely on winter snowfall that recharges the snowpack of the high mountains. The accumulated snow begins to melt in the spring, thus feeding the rivers of the region. Dams store the melted snowpack in reservoirs, making water resources available throughout the year. Although the large dams of the Colorado River were created in the 20th century to regulate variations in water flow throughout the year, produce energy, and distribute water in the region, today, the capacity of this infrastructure to control nature is challenged by the increase in extreme weather events such as intense droughts and floods intensified by anthropogenic climate change.

Faced with the risk of water shortages, states seek to build pipelines to satisfy societal needs, such as in the case of LPP. To study the impact of LPP on the Colorado River Basin, we first need to understand the political nature of infrastructure projects. This section is based on the premise that by identifying the shared qualities of the infrastructure, we can more clearly comprehend the Colorado River’s history and what is at stake in the construction of LPP. By placing this specific case within a larger historical and intellectual landscape, it is possible to make apparent the implications of extending water pipelines from Lake Powell to Washington County.

Infrastructure projects the future by embodying the promise of prosperity and economic development. Appel et al. (2018) argue that infrastructure represents the aspirations of progress and the desires for the modernity of nations, “That is why there is always greater investment in future-oriented infrastructures than is justified by their expense” (p. 19). The relevance of infrastructure lies not only in its functionality but also in the promises it embodies, as ideals of modernization of countries that are attractive to citizens. In this way: “Different visions of the future, different aspirations for one’s own life, and for the future of the community or nation, play an important role in shaping which infrastructure projects find support among populations”. In the case of Utah, LPP embodies the promise of development for Washington County. Having a reliable water supply in the future through pipelines ensures that new settlers and tourists arrive, and the local economy grows. Thus, as in the rest of the world, water infrastructure investment is essential to reduce climate events’ economic and social damage, such as floods and droughts.

Infrastructure projects are not simply technical objects placed at the service of collective welfare but represent the crystallization of asymmetrical power relations. Infrastructure selectively distributes benefits and hazards, such as energy, water, knowledge, money, decision-making capacity, poverty, pollution, and disease, to specific populations (Edwards 2010; Appel et al. 2018). This way, infrastructure design, creation, and maintenance shape society. For this reason, it is essential to ask (Appel et al. 2018, p. 2):

“To whom will resources be distributed, and from whom will they be withdrawn? What will be public goods and what will be private commodities, and for whom? Which communities will be provisioned with resources for social and physical reproduction, and which will not? Which communities will have to fight for the infrastructures necessary for physical and social reproduction?”.

The types of benefits Washington County can get from LPP are what the Indigenous nations of the region demand from the federal government, since they require financing to resolve their infrastructure deficit to satisfy their basic needs. Appel et al. (2018) highlight, “By tugging, pulling, and demanding infrastructures to recognize, serve, and subjectify them, publics also make themselves visible as demanding subjects of state care” (p. 23). In the water crisis in the United States, as will be explained in more detail in the next section, the current political struggle consists precisely of defining the priority in which farmers, Indigenous nations, cities, industries, or ecosystems are considered as “subjects of state care.” The creation of water pipelines is political worldwide because it defines (Appel et al. 2018, p. 22):

“ … not only who its subjects are, but also how they are collectively and differentially “treated” by the (public or private) institutions that administer infrastructures. Through everyday connections and disconnections, pipes, roads or electricity wires form populations that are unevenly governed and left aside …”

Consider the case of the Turkey-Northern Cyprus pipeline built in 2015. Water from the Anamur River is transported from the coast of Turkey to the Gecitköy Dam of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (a state not recognized internationally) to extend the geopolitical control of Turkey under a hydraulic patronage relationship (Mason 2020). The distribution of resources through pipelines is a means of exercising power. In LPP, as in any infrastructure project, its benefits and costs are unevenly distributed. For example, in the case of agriculture, the UDWR, in its Utah Water Plan (2021), recognizes that “there are still many questions about who should bear the costs and who should receive the benefits of agricultural water use optimization” (p. 100). The Colorado River’s water would benefit Washington County’s citizens to varying degrees, especially the water-intensive sectors such as agriculture and golf courses. Still, all its inhabitants would have to bear its economic costs.

Externally, pipelines such as LPP do not solve water shortage problems but redistribute them elsewhere. By using water from the Colorado River system, LPP affects other parts of the region since it impairs the living conditions of various ecosystems and limits the ability of other communities to adapt to climate variability. LPP is not simply buying water but also time, life, and political decision-making capacity. For example, priori-tizing this water distribution for southern Utah and not for Indigenous nations reproduces racial structures of exclusion. This problem illustrates how infrastructure projects tend to reinforce historical power relations; pipelines are commonly represented as “critical infrastructure” that promotes interests related to the economy and security of nations to legitimize their construction and block criticism, while hiding the social inequalities and environmental problems that are created (Spice 2018).

The proposal to build LPP leads us to larger questions. Can reliance on technological solutions to water supply problems multiply environmental problems? Instead of reducing Washington County’s vulnerability to drought, could LPP increase it in the medium and long term? In the case of the Turkey-Northern Cyprus pipeline, its defenders stated that this project builds resilience to climate change and reduces demand for water from the island’s aquifers. According to critics, this infrastructure conditions the island to intensive use of water, which encourages agricultural production, thus increasing vulnerability to climate change. In turn, urban expansion due to tourism can have a negative environmental impact by degrading rural landscapes (Mason 2020).

According to Di Baldassarre et al. (2018), creating reservoirs to respond to water supply problems has the secondary effect of increasing demands for water and population growth beyond those originally projected. Consequently, local communities are much more dependent on water infrastructure and, thus, more vulnerable to droughts. Similarly, engineering responses to water scarcity tend to push the problem into the future, such that irrigation efficiency multiplies the water demand (Grafton et al. 2018; Sears et al. 2018). Given the water level reduction in reservoirs due to drought, the southwestern United States has been forced to burn more fossil fuels to compensate for the loss of hydroelectric energy and the increase in demand, which increases global warming and, therefore, extreme droughts (Qiu et al. 2023). These examples illustrate Hornborg’s idea that modern technology displaces environmental problems to other times, spaces, and populations because it is “a strategy to locally save (human) time and (natural) space, at the expense of time and space lost elsewhere in the world-system” (Hornborg 2016, p. 73).

LPP could create and displace engineering problems in the future since Sand Hollow Reservoir, like all reservoirs and dams, has a limited useful life due to the accumulation of sediment. Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon have the same problem. Further, there are more unknown effects since infrastructure consists not of finished and predictable objects but rather fragile entities in permanent development because their construction, maintenance, and monitoring generate unplanned effects. Political, social, and environmental factors constantly affect infrastructure design and purpose (Edwards 2010; Harvey et al. 2017; Calkins, Rottenburg 2017; Appel et al. 2018). For example, although the operation of Glen Canyon Dam is currently threatened by a lack of water, in 1983 it almost collapsed because its operators filled the dam to a dangerously high level, seeking to produce more hydroelectric power for greater profits (Powell 2010).

Another example of the unintended consequences of infrastructure is the disappearance of wetlands in the United States and Mexico. The Colorado River does not flow freely through its basin because an extensive system of dams controls its water, and in most years its water does not reach the Gulf of California. As a result of this management system, there is less sediment in the river because it is trapped in the reservoirs; sediment was essential to the region’s ecology since it carried nutrients for fish and enriched previously flooded soils. The most dramatic impact of the modification of the river has been in the delta of the Colorado. The reduction of sediment and water levels because of overuse in the Lower Basin has been reducing the extent of the delta’s disappearing wetlands for several decades.

Each infrastructure project is designed according to the environmental conditions of its time. Mega-dams were created in the context of economic reactivation, expansion of cities in the West, and the climate conditions of the 20th century. Currently, extreme weather events, increased by anthropogenic climate change, challenge the ability of dams to deliver reliable hydroelectric power in periods of severe drought and to be safe in periods of heavy rain. Due to the high cost of maintaining mega-dams, their negative social impacts, their emissions of carbon dioxide and methane, and the large amount of water lost by evaporation from the reservoirs, governments are now considering not building new reservoirs, but rather dismantling them. The rapid reduction of the Colorado River is accelerating the political and scientific debate as to whether its water is sufficient to be stored in Lake Mead and Lake Powell or if, due to its scarcity, it is necessary to prioritize using a single reservoir. In the Colorado River Basin, the infrastructure of the past is in tension with the politics and environmental conditions of the present. In the 21st century, obtaining and extending a stable water supply through pipelines is less secure due to more significant climate variability.

Finally, it is worth clarifying that although the construction of large engineering works such as dams and water pipelines currently faces greater political obstacles, any new form of territorial administration requires some type of infrastructure. Although Utah is now in a dispute over whether the state should build infrastructure or expand its conservation strategies, this opposition is a rhetorical simplification because this distinction is not clear in the real world. The LPP debate is not about whether or not to use infrastructure to solve environmental problems but about what water use should have priority and what type of infrastructure is required for it. On the one hand, conservation involves the installation of measurement technology throughout the region to assess and optimize water use in concert with state goals. As the Colorado River Authority of Utah said, “Conservation is only good to the extent that we can measure.” There is no way to validate and legitimize conservation without data on its effectiveness. Therefore, the measurement infrastructure is necessary to make conservation tangible, transparent, and legitimate for public opinion.

On the other hand, due to historical interventions in the Colorado River Basin, the river itself can be considered as infrastructure organized to obtain specific benefits of the water cycle: electric power and water storage. Carse (2012) points out that infrastructure is not a “class of artifact, but a process of relationship-building.” This is to say that dams, locks, and forests are connected and become water management infrastructure through the ongoing work – technical, governmental, and administrative – of building and maintaining the sprawling socio-technical system” (p. 556). From Carse’s analytical perspective, we could say that LPP does not consist of building infrastructure from a natural river but of extending an infrastructural river. This concept implies extending the materiality of its water and the network of technical knowledge, administrative systems, economic benefits, ecological problems, and legal responsibilities anchored to it. Thus, the opposition between infrastructure and conservation is an unstable political demarcation that simplifies a complex debate to win allies in the search for a particular water use in Utah and accelerate the decision-making process.

6. Lake Powell pipeline’s political chess

The development of LPP is a complex political game because the negotiations on the future of the Colorado River operate at two bureaucratic speeds and articulate multiple interests, national actors, and political problems. First, in the southwestern United States, there are widespread obstacles to resolving environmental conflicts and creating responses to interstate water disputes because of political difficulties created by federalism. Second, regional stakeholders in southern Utah seek to secure access to river water even knowing of its decline since they hope to get one last chance to participate in the distribution of their use rights and because of the institutional inertia that defines their capacity for action.

First, water conflicts reveal the political limits of federalism. Although the Bureau of Reclamation is responsible for managing the Colorado River, the autonomy of each state of the basin has prevented effective regional planning, inter-jurisdictional collaboration, and long-term regional planning. While there is a long history of effective cooperation between states (for example, in the Law of the River treaties and the Drought Plans), and they avoid extensive legal battles that would force the intervention of the federal government (threatening their political autonomy); in the negotiations to respond to the Colorado River crisis there is competition between states to defend their historical privileges of access to its water and to avoid major water cuts.

The federalist political structure of the United States, within which the states must operate, can create political obstacles to addressing cross-boundary environmental issues. Therefore, local water supply decisions are often insufficient or fail to address regional water stress problems. The division of powers between the federal government, states, and local governments has generated a lack of leadership and has prevented the development of articulated environmental policies, which is why there is a weak national climate change policy in the country. Congress has broad constraints in designing and implementing environmental policies due to partisan polarization and the wide influence of interest groups in candidate choice and public debate, which leads to policy gridlock. These political conditions have prompted states and local governments to take their own climate adaptation paths and goals to respond to the lack of national agreements, obligations, and congressional action (Kraft 2019; Kraft, Vig 2019).

As an example of the challenges of addressing transboundary problems of water among sovereign entities, in May 2023 the lower basin states agreed to conserve a large amount of water to keep the Colorado River system running. But since 2022, the Bureau de Reclamation has tried unsuccessfully to coordinate with the states of the basin a reduction of 2400-4900 MCM of water use. For this reason, to avoid a deadlock in the policy debate, as with the 2007 Interim Guidelines and the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan, the Bureau of Reclamation threatened the states that it would mandate unilateral water cuts in the basin due to the lack of consensus and unified plans for response. This is a political strategy to speed up regional action. The federal government threats have served to neutralize internal conflicts, as according to Fleck and Castle (2022), they “provide political cover for state officials to agree to measures that are not universally supported by their constituents (e.g., “If we didn’t agree to X, the feds would order Y, which would be much worse!”)”. Even so, bureaucratic sluggishness continues to characterize the basin’s response to collective environmental problems due to the vast diversity of interests at stake.

The construction of LPP is uncertain in the context of the water crisis of the Colorado River. Although Utah water authorities have been forced to recognize that future Colorado River water development depends only on available water within the 23% agreed in the Law of the River, in 2026 the states must abandon the fixed allocations of water they receive and create a new distribution strategy, which affects the water that Utah will be able to use in the future. This dynamic will create further disagreements with the states on what mechanisms, hierarchies, and quantities of water-use cuts are necessary to keep dams running. At the same time, Lake Powell’s future is unclear for LPP (see Fig. 4); in the next few years, energy production and the water reserve may be prioritized in Lake Mead since there will not be enough water in the basin to fill two large reservoirs.

In this complex panorama, Indigenous nations want to formalize and exercise their water access rights, of which they have been historically deprived. Still, states and water districts claim no more water is available because the water rights these nations can obtain are taken from state allocations. Hence, tribal water rights tend to be unrecognized. Thirty Indigenous nations of the basin have rights to about 26% of the river’s annual flow, but even if the courts have defined their water rights, most of them do not necessarily have the infrastructure to use it. Therefore, these rights are undeveloped. Hence, these nations have low access to drinking water. For this reason, Indigenous nations fear that the water rights that correspond to them will be lost in the future, such as the water sought to be used by LPP, which the Ute Indian nation claims in the negotiations of the Colorado River Compact in 2026.

There is a historical distrust of water negotiations with the federal government on the part of indigenous communities. For example, the dispute with the Utes began in the 1950s with the Central Utah Project (CUP), which was designed to transport water from the Colorado River to the Wasatch Front and Utah counties. The water managers of the project agreed to extend these infrastructure works to the Indigenous nation in exchange for using part of their territories. After the first phases of development, the state and the federal government did not comply with the agreement. Although currently there is an institutional commitment to protect the water rights of Indigenous nations, in the 1990s the Bureau determined that the water the Utes sought to obtain did not have a beneficial use, and without consulting the community, passed their rights to the UBWR, which divided these rights of use into different districts and private developers (Penrod 2021).

Seeking to end this legacy of exclusion and place water management at the center of the discussion as a matter of historical justice, the Indigenous nations of the Colorado Basin demand to participate in the negotiations of the Colorado River as sovereign nations since they have legal rights to about a quarter of the river, and because they consider that the basin states do not represent them. Also, wanting to be a part of the solution, they demand to have a vote in the discussions about the region’s response to climate change. Currently, there is partial progress on this issue. In 2023, Upper Basin officials proposed including Indigenous nations in collective Colorado River negotiation, and in 2024, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission created a new veto mechanism that gives Indigenous nations the power to block hydropower projects that affect their territories.

One of the biggest obstacles in discussions about the Colorado River is that there are different levels of concern about current problems and future threats to the water supply. In March 2022, I attended an academic event in Utah about the future of the Colorado River that allowed me to identify a close relationship between the role of the speakers and the sense of urgency about the water crisis, specifically whether solutions should be developed in the short, medium, or long term. Each type of institutional work generates a range of action, authoritative criticism, and imagination of what is possible. On the one hand, the event attendees who worked close to the states as lawyers, representatives of public institutions, irrigation districts, water authorities, and state scientists affirm that they know the states’ institutional limits, possibilities, and imperfections. So, they know how to maneuver and make an imperfect system more flexible since institutions have the discretion to make their regulations operational. In this way, they want to work within the existing system of rules, such as the doctrine of prior appropriation and the Law of the River, because there is predictable order that reduces political conflict. On the other hand, actors far from the state, such as university scientists, Indigenous leaders, and environmental activists, argue that they see the slowness in the state’s response to the environmental crisis and the obstacles that generate lobbies by protecting particular economic interests. This type of actor highlights the importance of transforming the political system since its design makes it impossible to respond to the water crisis.

The actors closest to the states seek short-term solutions to the Colorado River crisis, arguing that there is no time to solve structural problems given the rapid reduction of river flow, the current institutional mechanisms that cannot solve several problems at once, and the challenge of articulating political wills around multiple issues. On the other hand, actors furthest from the state seek to discuss medium and long-term solutions because they tend to consider that if the problems of social exclusion of Indigenous nations and environmental protection of the basin are not solved, future solutions will not be effective, considering that these two issues are thought to have caused the current water crisis.

We do not know with certainty how fast the environmental conditions of the Colorado River basin will be transformed by climate change and natural variability, or therefore whether the new actions designed by the basin states and the Bureau of Reclamation will be enough. While there is a range of maneuvers within current laws, if the water supply problems accelerate much more than models suggest, the current policies and mechanisms of planning and collaboration of the region will not be enough to address the water crisis to the point that federalism can spur a struggle for water appropriation. The near future of the American Southwest is fragile.

The second level at which this political game operates is the regional scenario in which the risks of climate change are defined. LPP proponents, as water authorities of the region, justify its construction by stating that this project must use the Colorado River water because climate change will drastically reduce the water supply of Washington County. The environmental dangers of a global threat legitimize a local response. Critics of this infrastructure, such as the Utah Rivers Council, argue that trying to extract more water from the Colorado River denies the reality of climate change since it will negatively affect the river’s flow throughout the region.

Interestingly, in Utah, the same conservative politicians who were climate change skeptics in previous years are now mobilizing around this infrastructure project to direct public investment and territorial planning.

The construction of LPP continues to be promoted despite the continuous reduction of the Colorado River because of two factors. First, in the medium and long term, the political actors of Saint George want to be able to participate in the transfer of water rights in the region before there are more significant political constraints. Kuhn explains (Jacobs 2021):

“These large municipal districts are lining up their strategy to make sure as the river continues to diminish because of climate change, they have access to the most senior rights – and those senior rights are agriculture. If you have the pipelines and canals in place, you’re in good shape.”

If Washington County does not obtain access to new water sources and its population continues to increase in the coming years, it may be forced, like Oakley County in Utah in 2021, to establish a moratorium on new construction due to limited water supply. This scenario can be multiplied in the rest of the Southwest United States.

Second, institutional inertia plays a crucial role in the capacity for action and criticism of the water authorities. An essential question in the LPP case is why water authorities insist on building expensive infrastructure projects such as pipelines that generate environmental concerns and broad political disputes. People defend or reject actions on the Colorado River or LPP because they consider this what their community expects from them. If they change their opinion, they risk their reputation by questioning their predecessors’ decisions, knowledge, and financing. In short, the ideals that shape the opinions in environmental conflicts do not circulate freely in the social world but are stabilized by institutional inertia. In an academic debate on the Colorado River previously mentioned, a water authority argued that its job was not to discuss the state’s economic development model or population growth but to guarantee its short-term water supply. These authorities cannot deviate from their states’ legal framework and political guidelines. The legal mandates of their institutions predetermine their range of action.

Understanding water supply issues and the institutional inertia in Utah and worldwide requires analyzing the complex physical and legal connection between water and oil. On the one hand, there is a visible physical link, since oil distribution and using fertilizers and pesticides generate water pollution. In turn, oil accelerates social metabolism because of the machines it drives and the fertilizers it produces, which causes agricultural hyper-productivity, leading to water overconsumption. Finally, oil use releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which multiplies extreme weather events, such as droughts. On the other hand, these two powerful substances have an invisible legal connection since the current institutional perspectives and instruments to address the water crisis are partially configured by the first environmental laws created to address oil pollution in the 70s.

According to Bond (2022), the scientific and legal instruments of the first environmental laws were configured in negotiations with the oil industry seeking to control the impact of oil extraction without compromising its financial profitability. These early environmental regulations were designed to manage environmental problems while avoiding addressing their causes. It is possible to push Bond’s ideas further and argue that the logic of the first environmental regulations is still reproduced in subsequent policies, hence the current limitations of institutional strategies to address the water crisis. Oil policy came to frame water policy, enabling and reducing the current political and scientific response capabilities. Oil slowly infiltrates the very depths of our bodies through the contamination of water, air, food, and objects, but also through the regulatory oil regime, which extends into how we understand and manage water.

Utah water authorities may seem conservative in their proposals to respond to the water crisis because they follow the original logic embedded in the framework of environmental policies. In decision-making, they can only see problems and solutions within the context authorized by their legal, economic, and technological frameworks. For this reason, the construction of LPP is not designed to address the structural causes of the water supply problems in Utah. As an example of the inertia that affects institutional decisions, the Legislative Auditor General (2015, p. 3) found that Utah Division of Water Resources:

“… has a challenge to balance the competing elements of its mission. To some extent promoting the full development and utilization of water in the state is at odds with promoting conservation. In fact, in a legislative committee, one member questioned whether Utah should wait to promote conservation until after the state has developed its full allocation of interstate waters. Other policymakers hold the competing view that more focused conservation efforts are needed before investing in large-scale infrastructure projects …”

In the regional political game, environmental conditions work against LPP. The dramatic images presented by the media about the impacts of drought on farms and reservoirs in the Southwest of the country, especially in the Great Salt Lake, have generated enormous national interest. Reports such as “Utah’s ‘Environmental Nuclear Bomb ’” of the New York Times in July 2022, warning about the drastic reduction of the lake and the public health impacts of its toxic dust, raised significant concerns about water use in Utah. Recently, the local press has taken a critical position on LPP. In August 2022, an editorial of the Salt Lake Tribune invited its readers to think about the long-term future of the Colorado River, which would imply abandoning the construction of LPP because “Lake Powell just isn’t going to have nearly enough water to justify the cost of such a pipeline”. It added, “Utah must prepare itself for two distinct possibilities. Either the United States will abandon and drain Lake Powell, or Mother Nature will. Our state’s power to oppose either is slim at best” (The Salt Lake Tribune 2022).

Despite adverse political and environmental conditions, the Colorado River Authority of Utah maintains that “all options are on the table” to respond to the water crisis in the state, including LPP. In 2022, pro-LPP representatives continued to insist that the LPP should be built, arguing that it is the only way to guarantee Washington County’s future water supply. The associate general manager for the Washington County Water Conservancy District affirmed that: “The Colorado River isn’t going to zero (…) Less water doesn’t mean no water (…) It’s just that we have to be realistic about making sure (the pipeline) can function and operate within the bounds of what Mother Nature gives us and in the bounds of Utah’s allocation of the Colorado River” (Kessler 2022). Similarly, although Governor Cox recognizes the environmental uncertainties of the Colorado River, he assured that he remains committed to supporting this project.

In response to the Great Salt Lake decline, in January 2023, legislators from Utah proposed protecting the lake for five years with money earmarked for LPP and Bear River Development. Although this project was rejected, hopes about the construction of LPP began to disappear. In February, there was a change in the political rhetoric of the LPP. St. George Mayor Michele Randall told the press that while “We are still keeping our fingers crossed on the Lake Powell pipeline”, the city is now focusing on building new reservoirs, reusing water, and expanding conservation. Despite the scientific warnings about the decreasing future of the Colorado River, the polarization around LPP is likely to continue in Utah due to the strong winter of 2022 that, in the spring of 2023, recharged the reservoirs of the region and raised the level of the Great Salt Lake. Finally, in December 2023, various environmental organizations sent a joint letter to request the Department of the Interior to reject LPP. For its part, Washington County Water Conservancy District continues to insist that LPP water is essential to the future of southern Utah.

7. Conclusion

The decrease in the water level of Lake Powell in recent years is a complex environmental sign of the effects of climate change, territorial planning difficulties derived from federalism, the consequences of relying on large infrastructure projects for economic development, and the overuse of natural resources driven by agriculture and the region’s rapid population growth. As Glen Canyon reemerges from among the waters of this artificial lake, scientific and political controversies multiply on how to manage the Colorado River sustainably. Amid this panorama, the proposal to transport the water from this river to southern Utah through the Lake Powell Pipeline is being debated to guarantee the water supply in a region threatened by its future scarcity.

This case study analyzed the history, controversies, implications, and uncertainty in the construction of the Lake Powell Pipeline to show how Utah has been addressing the larger problem of responding to growing demands for water in the face of a well-documented need to reduce water use throughout the basin. To this end, first, a historical panorama of the technological and political intervention that has allowed the management of the Colorado River was presented. The role of hydraulic infrastructure and the Law of the River in shaping the landscapes of the basin was identified. Second, the arguments for and against LPP were described. On the one hand, proponents argue that this project is necessary to guarantee the future water supply of Washington County since it is threatened by climate change and because conservation strategies will be insufficient to meet the increase in water demand. On the other hand, this project was denounced by its critics since they considered it unnecessary and extremely expensive, its data was misleading, and it could increase the water crisis in the basin.

Third, it was identified that the problems of regional planning intersect the histories of the Colorado River and LPP since the gradual reduction of the river generates broad environmental uncertainties and political debates about its use, which calls into question the construction of LPP. Fourth, the properties of the infrastructures were analyzed to highlight that even as pipelines are essential to satisfy societal needs, they create new forms of inequity through the distribution of benefits and dangers to other regions, times, and populations. For this reason, it was stated that the construction of LPP could lead to the naturalization and reproduction of inequitable forms of access to water. Then, it was highlighted that the LPP controversies are not about the opposition between infrastructure versus conservation but about the legitimate use of water and what kind of infrastructure should be built for it.

Fifth, multiple interests inscribed in the development and opposition to LPP were highlighted, which makes its negotiation a complex political game. Water access problems require regional coordination plans, but the division of administrative authorities by the federalist structure complicates creating unified responses to cross-boundary environmental issues. At the same time, it was argued that the management of the Colorado River basin has enormous political complexity because its water is part of disputes with Indigenous nations that seek to obtain and exercise their historical access rights. This paper also reflected on local interests in constructing the LPP to participate in purchasing senior rights and the effect of institutional legacies as a delimited framework of action in the decision-making criteria of water authorities.

Infrastructure projects are attractive solutions to water supply problems because they can be built in a few years to respond to droughts, generate the illusion of control over nature’s threats, and generate short-term electoral and political benefits by creating jobs and guaranteeing access to resources for industries and populations. For this reason, LPP is not an isolated case in the United States. Its controversies exemplify a shared phenomenon worldwide in which priority is given to building local water infrastructure while ignoring the need to create more holistic river basin policies. This happens when decision-makers and citizens ignore the long-term environmental, political, and socio-economic costs of reservoirs and pipelines.

Historically, nations’ responses to droughts have been reactive. Instead of risk reduction, there has been a focus on crisis management, which generates dependency on governments and discourages better management of local resources (Wilhite 2011). Currently, the world panorama is changing and is more heterogeneous. Buurman et al. (2017), in their comparative study on drought management in ten cities, found that although official responses appear reactive, short- and long-term plans are commonly mixed. Nevertheless, they critically highlight that response measures are primarily limited to reducing demand in the short term and increasing supply in the long term. This last aspect is important because a supply-based approach is problematic, as in the LPP case. Expanding water sources generates environmental impacts (for example, excessive exploitation of underground water), political conflicts (shared resources in borders), and physical limitations (contami-nation in reservoirs that reduces their capacity for use) (Sülün 2023).

Despite the promises of continuous growth, local populations must eventually face the negative consequences of the benefits obtained by their infrastructure because greater economic productivity goes hand in hand with greater environmental deterioration, which is precisely the American Southwest’s history. The wealth of this region is directly linked to intensive use of Colorado River water, but economic growth has physical limits. Even the most conservative projections for the river indicate that its reduction will continue in the coming years to the point where there will not be enough water to respond to growing demand. The water crisis in Utah is an environmental bubble about to burst if there is no comprehensive planning that transcends the obstacles generated by federalism to face the climate challenges of the 21st century. In this panorama, it is urgent to redesign the Colorado River Compact in 2026 to create a comprehensive and robust inter-basin management system that allows addressing local conflicts inherent to water management without compromising long-term environmental sustainability objectives.